The stars aligned this month at a UC Berkeley Library event focused on the total solar eclipse.

Combining elements of a book talk, exhibit, and workshop, the event stoked excitement for April’s much-anticipated astronomical phenomenon. The total solar eclipse — when the moon completely blocks the sun’s face — will darken skies on April 8.

Enthusiasts arriving at the Art History/Classics Library were met with a constellation of eclipse-themed maps, books, and images gathered from various library collections, and the soft sounds of celestial-inspired music. Featured speakers then shared reflections on studying and experiencing these rare cosmic occurrences.

“When the sun is blocked from perception for a few minutes in the track of totality, everything and everyone reacts to it,” said Henrike C. Lange, associate professor in Berkeley’s departments of History of Art and Italian Studies and co-organizer of the event. “No wonder this phenomenon has captured our imagination.”

Here are three things we learned from this stellar event.

1. Total solar eclipses bring people together.

Lange recently released Eclipse & Revelation: Total Solar Eclipses in Science, History, Literature, and the Arts, a collection of essays from 14 international experts representing more than two dozen fields. Each chapter explores solar eclipses through a distinct disciplinary lens, from meteorology to music, and from art history to animal behavior. The book was co-edited by the late Tom McLeish, a renowned theoretical physicist who died in 2023.

“(Our work) has always had two separate goals,” Lange said in her presentation. “(We wanted) to explore not just the phenomenon, representation, and effect of the eclipse, but, even more important to Tom and myself, to experiment with healing the break between two siloed cultures — the sciences on the one hand, and the arts, humanities, and theology on the other.”

Lange noted that Eclipse & Revelation was carefully developed over seven years for a wide general audience. Each chapter starts with a basic summary of its content and a glossary that outlines key terms. The book is an invitation to see the world through the eyes of experts in many fields and disciplines and to recognize that we have much to learn from one another. It also contains a toolkit for eclipse-chasers.

The eclipse event, part of an ongoing Maps and More pop-up exhibit series, mirrored the book’s interdisciplinary approach — bringing together people from across campus, and beyond. A similar gathering was hosted by the Library to commemorate the Great American Eclipse of 2017.

“I think the spirit of these events is that you get a lot of people from different disciplines coming to interact in less formal ways than they may on a day-to-day basis,” said Sam Teplitzky, UC Berkeley’s open science librarian and a co-organizer of the program. “And there are a lot of interesting conversations sparked by the materials, by the topic at hand, and it’s just a really rich experience that gets people out of their silos.”

2. To see a total solar eclipse, you will likely need to travel. And you should.

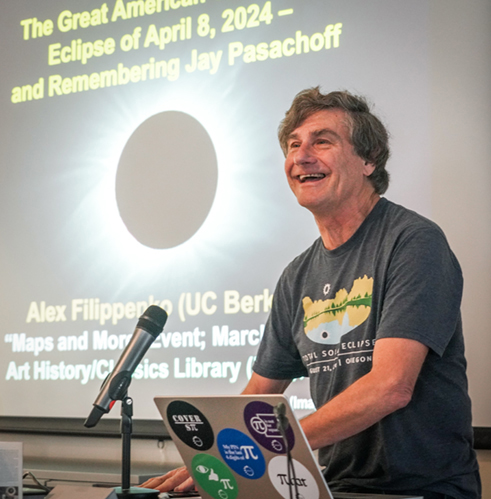

Astrophysicist Alex Filippenko, a distinguished professor of astronomy at UC Berkeley, has witnessed 19 total solar eclipses — and he encouraged everyone to see at least one.

Why? Because it’s such a rare opportunity.

Filippenko said a typical path covers 0.5 percent to 1 percent of the Earth’s surface, so any given location will experience a total solar eclipse only every 380 years or so.

That means you will likely need to travel to view one. Filippenko suggested using eclipses as an excuse to visit far-flung locations, as he has.

Bay Area eclipse-chasers will have to hit the road for April’s display. The eclipse path crosses North America diagonally, starting from Mexico. Major cities such as San Antonio, Texas, and Cleveland, Ohio, are in line to experience full totality, weather permitting.

Filippenko, who is a co-author of the award-winning textbook The Cosmos: Astronomy in the New Millennium, said viewers in the path will witness something unique. “The sun’s magnetic field changes with time, so never does the corona (the outermost part of the sun’s atmosphere) look the same from one eclipse to another,” he explained. “And that’s another reason to see more than one of them.”

He added that totality happens quickly, and it’s nearly impossible to see all of the phenomena associated with an eclipse in one viewing. His lifetime average is about two minutes of totality per eclipse.

Filippenko recommended that people check the weather in advance, and leave plenty of time to drive to a location with clearer skies, if needed.

He also celebrated the late Jay M. Pasachoff, co-author of The Cosmos, at the conclusion of his remarks. Pasachoff contributed a chapter on the solar corona to Lange and McLeish’s Eclipse & Revelation. Both Lange and Filippenko shared memories of the experience of co-writing with McLeish and Pasachoff, respectively, and emphasized the theme of books as a medium that transcends time and space.

3. You can explore the cosmos — at a library.

The eclipse event culminated with presentations by Hannah Hellman, from Sonoma State University, and Juan Carlos Martinez Oliveros, from Cal’s Space Sciences Laboratory. The pair are working on the Eclipse Megamovie 2024 project.

The project asks citizen scientists along the path of totality to capture photos of the eclipse. The resulting images are used to study the motion of the corona, and the way it looks and behaves at multiple points on the path. Martinez Oliveros shared some of the results from the 2017 project, which collected tens of thousands of images from volunteers.

Hellman also offered a fascinating interdisciplinary perspective on literature in her presentation on author Virginia Woolf’s 1927 eclipse experience.

Teplitzky and co-organizer Lynn Cunningham, Berkeley’s art librarian, were excited to put together an event that offered visitors a variety of entry points into the experience of the total solar eclipse. They hope the event raised awareness about the phenomenon and the multitude of related materials that are available at the UC Berkeley Library. Those who were not able to attend can find many of the featured materials in an eclipse-focused library guide.

“Events like this do a kind of dual duty, enlightening people as to the richness of our collections that aren’t always apparent and aligning with the Library’s mission to open ourselves up to the public at large,” Teplitzky said.